Kenya abductions: The powerful legal shields citizens and courts can use – Expert

As the courts have made clear, the government cannot use national security as a justification to violate people's fundamental rights.

By John Mukum Mbaku

The Kenya National Human Rights Commission recorded 82 abductions or enforced disappearances between June and December 2024. Many of the people reported missing after the country’s anti-tax protests later resurfaced, but some have been found dead. Dozens of young Kenyans reported being snatched from their homes or the streets by armed men.

More To Read

- How crackdowns on protests exposed escalating human rights abuses in Kenya

- Pressure mounts on NIS boss Noordin Haji as lobby calls for his resignation over abduction scandal

- Ex-IPOA chief Macharia Njeru calls for action against abductions and impunity

- Bring it on! - CS Muturi scoffs at impeachment threats

The origins of enforced disappearances and the institutions that facilitate them in Kenya can be traced to British settler colonialism. Kidnapping and detaining political dissidents and pro-independence fighters without trial, and making them disappear, was a political tactic during Britain’s colonisation of Kenya.

It was employed effectively to control certain individuals and groups and enhance the colonial control of land and the people.

Other Topics To Read

- Politics

- Abductions

- Constitution

- Constitution of Kenya

- enforced disappearances

- extrajudicial killings

- kenya human rights

- Kenya Judiciary

- Kenya National Human Rights Commission

- Kenya National Police Service

- kenya politics

- kenya protests

- Peace and Security

- Rule of law

- William Ruto

- Kenya abductions: The powerful legal shields citizens and courts can use – Expert

- Headlines

Independence in 1963 was supposed to establish a new political dispensation in Kenya: one characterised by the rule of law and institutions capable of guaranteeing accountability in government.

However, enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings remained a pervasive problem. The targets are now citizens who are considered a threat to the incumbent government’s survival.

Fifteen years ago the country tried to chart a new course with a new constitution. One of its aims was to eliminate enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings. Instead, peace and security would be secured through the rule of law, respect for human rights and a reliance on the courts to settle disputes. Hence, the Constitution established new institutions. They included an independent judiciary capable of minimising government impunity and enhancing the rule of law.

Unfortunately, serious challenges remain as security forces continue to act above the law. I have studied democratic governance and the application of human rights laws in African countries, including Kenya, for over three decades. I would argue that the fundamental problem in Kenya is the failure of some government officials to accept and respect the supremacy of the law.

For a democracy like Kenya’s to function, the law must be superior to the government. To build a peaceful and secure country, state officials must agree to resolve conflicts peacefully through the courts.

The scale of the problem

Following reports that at least 82 Kenyans had disappeared since June 2024, civil society groups noted that “the disappearances seem to display a strategic pattern, targeting individuals who have been critical of the government”.

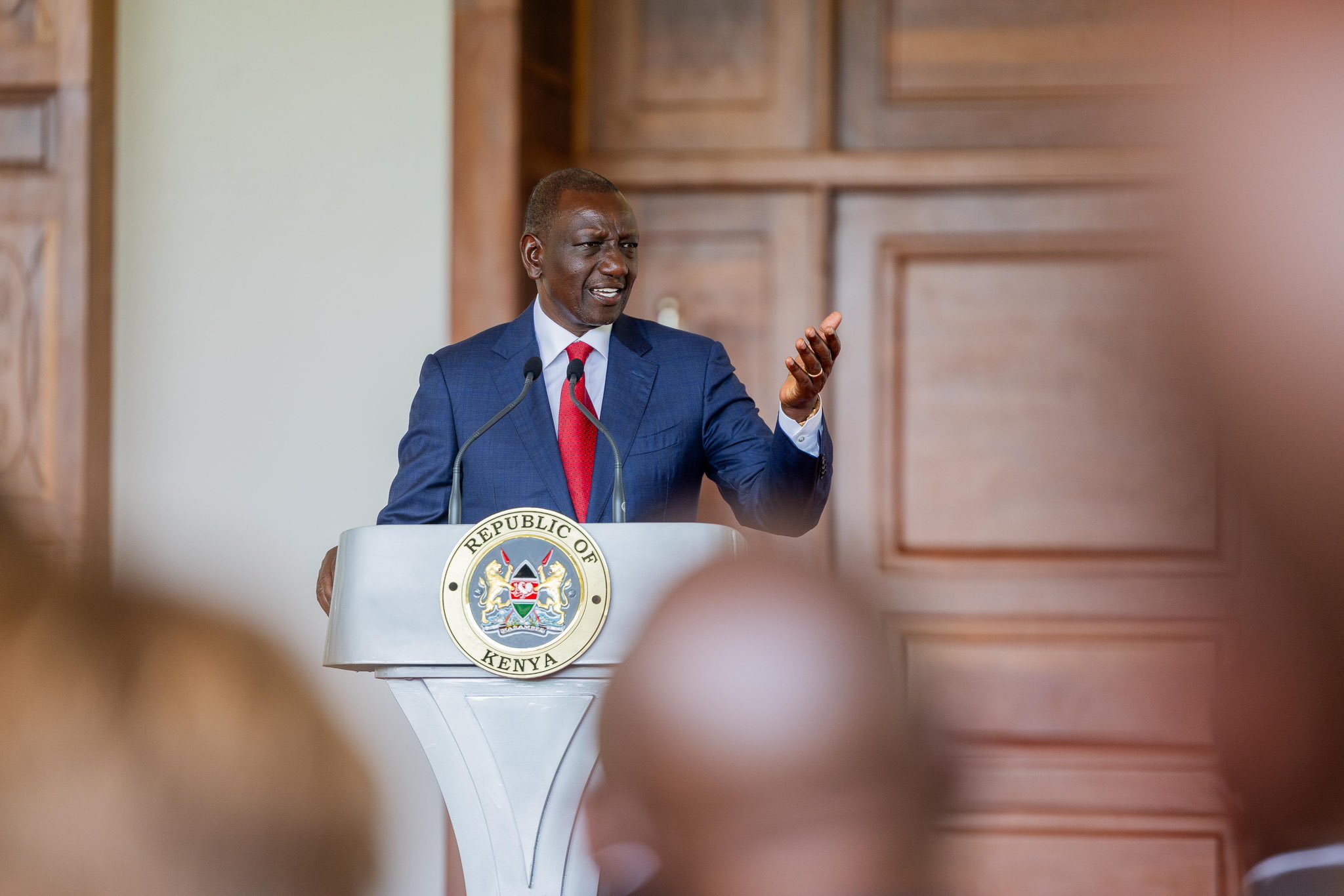

The number of abductions spiked in the wake of widespread protests against the government of President William Ruto. In June 2024, the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights and the Police Reforms Working Group documented “23 deaths, 34 forcedly disappeared, and 164 arrests” following the protests.

Evidence of extrajudicial killings and kidnappings has been mounting for years. In October 2021, a Senate committee report documented several cases. For example, on 6 April 2019, the committee met with civil society organisations in Kwale County in Kenya’s coastal region. The legislators heard that 45 cases of extrajudicial killings and 16 cases of forced disappearances had been documented over three years.

Earlier in 2013, the UN Committee against Torture released a report on Kenya raising concerns about “the persistent allegations of ongoing extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances and excessive use of force by police officers”.

The response

The government continues to insist that it doesn’t “condone or engage in extrajudicial killings or abductions”. Yet the available evidence points to the contrary. For instance, there have been discrepancies reported between the causes of death recorded by the police in morgue logbooks and autopsy reports in three cases involving anti-government protesters.

In November 2024, Ruto referred to alleged abductions as “fake news”. By late December, he had changed his tune and said he would bring a stop to the abductions of government critics.

Human rights activists described the president’s statement as “an admission that they’re (abductions) happening under their watch, if not by them”.

What’s at stake

If the allegations made against security forces were proven, the state would have violated several rights guaranteed to Kenyans by the constitution and international human rights treaties to which Kenya is a state party.

Domestically, these guarantees include the rights to life, human dignity, and freedom and security of the person. Kenyans are also guaranteed the right to peacefully assemble, demonstrate, picket and petition.

There are also laws related to the use of force. The National Police Service Act states that a police officer must always strive to “use non-violent means first” and that “force may only be employed when non-violent means are ineffective”.

If force must be used, it must be proportional to the objective to be achieved, the seriousness of the offence, and the resistance of the person against whom it is used, and only to the extent necessary while adhering to the provisions of the law.

Kenya is a constitutional democracy, meaning laws guide its government. If the government becomes a lawbreaker, it risks breeding contempt and inviting anarchy.

The judiciary

Kenya courts have developed a robust jurisprudence on the use of force by the police and security forces.

In a case that challenged police actions during the 2020 curfew to fight the spread of Covid-19, the high court held that “one cannot suppress or contain a virus by beating people”. The court held that the National Police Service “must be held responsible and accountable for violating the rights to life and dignity, among other rights”.

In a case in 2014 that concerned the shooting of an escaping suspect by the police, the court held that “the shooting was unreasonable and the use of force unnecessary and unlawful”.

In 2010, the court of appeal held that while the law permits the police “to use all means necessary to effect arrest”, they “are not allowed to use greater force than reasonable or necessary.”

The rulings in these cases remind Kenya’s security forces and government organs that they must act according to the law and respect the rights enshrined in the country’s Bill of rights.

Fixing the gaps

Kenya’s rule-of-law system is still evolving. Since the constitution came into effect in 2010, the country has developed a relatively effective judicial system. The courts have developed a significantly progressive human rights jurisprudence.

But while the tools are there, they must be used. This will require the executive branch of government to act expeditiously to ensure that its various organs, such as the National Police Service, remind members to perform their duties according to the law and in respect of Kenyans’ fundamental freedoms.

The executive must recognise and respect the courts’ constitutional role in protecting Kenyans' rights. As the courts have made clear, the government cannot use national security as a justification to violate people's fundamental rights.

The constitution provides a powerful tool for Kenyans to punish poorly performing politicians. While they can legally and peacefully protest against government impunity, the Constitution gives them a much stronger weapon: elections. Incumbent politicians must recognise that their unwillingness to fully confront impunity could cost them re-election.

John Mukum Mbaku is a professor at Weber State University

Top Stories Today